The internet is abuzz this morning with news that a previously undiscovered tribe has been found in the remote Javari Valley region of Brazil, on the Peruvian border. There are an estimated 70 “undiscovered” tribes left in the world, people who have not ever made contact with the civilized world — most of them from the Amazon rainforest of Western Brazil — and so the existence of even one more tribe is rare and exciting news. The last discovery of an uncontacted tribe came two years ago, when unknown Indians in Brazil came out of the trees to try to shoot down a government photographer’s plane with arrows.

Indiana Jones was for real.

Yesterday morning, I was video-chatting with a friend in Australia, where it was late at night. The other day, I ate plums that were grown in Chile. Lord knows which sea the fish I eat comes from, or what brown hand sews my shirts. As fond as we are of musing about our rapidly shrinking, ever more interconnected globe, it is important to remember that there are still people in the world who exist outside of both our economy and our knowledge. There are villages where no Coca-Cola t-shirts hang on laundry lines, no hunter runs the forest in Reeboks, where no white anthropologist plays with the children between notes in his orange book. These people are neither fighting with oil companies nor being taught how to grow sustainable shade-grown coffee by non-profit do-gooders. As far as we know, these uncontacted tribes have no idea that we, the rest of the world, exist. Civilizations have risen and fallen, monuments and cities have been built, been demolished, and regrown on the rubble; world wars have been fought and revolutions both violent and scientific, artistic, philosophical, and musical have shaken governments and their people; empires have stretched their tentacles into almost every crevice of the Earth. The Eighties happened. Beyonce recently dropped her hot new single. Man landed on the moon. But for a few villages in the Amazon, none of this is true. Their reality does not include us, or what we call “history.” Their world is still the fish at the end of the spear. It is the dragonfly and its god, the rainwater and the fruiting of the blue-flowered tree, and the one and only language.

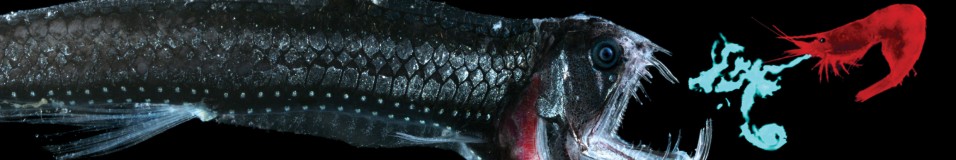

We also know that we cannot contact these tribes, because of the risk of contagion. When the Matis people of Brazil made first contact with the government after years of avoiding them as an enemy, more than half the tribe died of pneumonia; a modern-world retelling of the story of thousands of European/Indian contacts throughout history. The recently-discovered tribe in the Vale do Javari will remain a mystery to us, and we to them; we may never learn their names or customs or language, nor gain their unique knowledge of their remote corner of the planet. In fact, because we will not attempt to contact them, nor the eight to two dozen other uncontacted species in the Javari, we’ll never be able to see their forest home nor the flora and fauna therein. This got me thinking: If we never make contact with the new tribe, what else will we never contact? Brazil is second only to Indonesia in number of endemic species, and the Amazon rainforest is one of the most biodiverse regions in the world. It seems logical that there would be at least a dozen species endemic only to that region. The Unknown People know what they are. Can we, sight unseen?

Beautiful Metropolitan Downtown... Somewhere

Continue reading